Mitigating Risk Factors for International School Students

Tanya crossman and lauren mccall

When TCK Training released our white paper, Caution and Hope: The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids, we were only beginning to scratch the surface of the data we collected from 1,904 individuals who completed our 2021 survey on childhood trauma in globally mobile Third Culture Kids. In our second white paper, TCKs at Risk: Risk Factors and Risk Mitigation for Globally Mobile Families, we looked at 12 risk factors and ways to mitigate these risks. This article is part of a series of blog posts that looks a little deeper at certain sub-groups represented in the data.

Mitigating Risk Factors for International School Students

In the course of our research into Adverse Childhood Experiences among globally mobile young people, we learned a lot of difficult truths about what international school students experienced. This blog post will discuss the prevalence of various types of abuse and neglect, but there are no graphic descriptions.

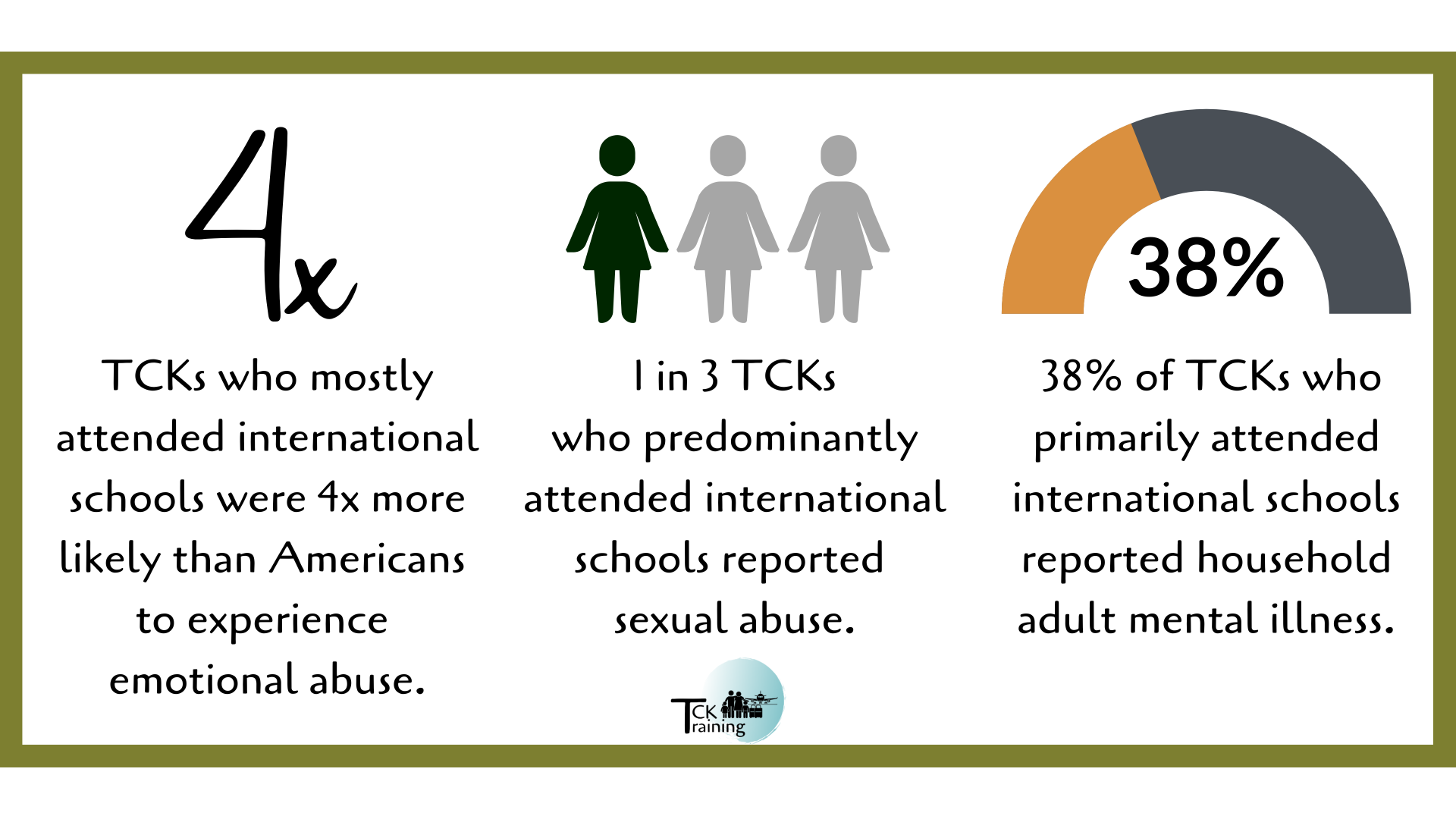

According to our research, TCKs who were predominantly educated in international schools were four times more likely than Americans to experience emotional abuse. Our survey also found that 1 out of every 3 international school TCKs experienced sexual abuse and 38% born after 1980 reported that an adult with mental illness lived in their childhood home.

According to our research, TCKs who were predominantly educated in international schools were four times more likely than Americans to experience emotional abuse. Our survey also found that 1 out of every 3 international school TCKs experienced sexual abuse and 38% born after 1980 reported that an adult with mental illness lived in their childhood home.

Internationally mobile families and children are often viewed as privileged, and therefore not at risk of ACEs, PTSD, or other mental health struggles. This data suggests the opposite.

Among the demographic factors we collected were the primary reason the family moved internationally (sector), and their core educational experience. The education types were: local/national school, international school (including DoD schools), Christian international school (including missionary schools), boarding school, and homeschool (including online school/homeschool co-ops). We found a strong correlation between sector and education:

Nearly one third (31%) of the 1,904 TCKs we surveyed attended international schools primarily. This is in addition to 20% who attended Christian international schools (including both larger Christian-worldview schools and smaller missionary schools). With deeper data analysis, it became clear that three educational types (Christian schools, homeschool, and boarding school) were primarily attended by missionary kids. When we looked at the non-mission kids in our sample, the percentage attending international schools rose to over half (53%).

For this reason, we are using two types of charts in this blog post. We compare risk factors in different educational experiences, but also compare the rates seen in international school students to both missionary and non-missionary groups overall.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Research into ACEs has taken place worldwide across 25 years. The ten ACE factors are divided into Child Maltreatment (abuse and neglect directly suffered as a child) and Household Dysfunction (factors affecting the childhood living environment). The ACE questionnaire asks about childhood experiences without using the words "abuse" or "neglect" - helpful for catching abusive or neglectful experiences a person would not label that way themselves. We often compare our results to the CDC-Kaiser study of 17,000 Americans, as this is the largest ACE study done worldwide to date. Comparisons with other global populations can be found in our white paper.

We often saw different results across categories among TCKs born before/after 1980 – with the Boomer/Gen X generations on one side, and the Millennial/Gen Z generations on the other. This also separates groups who were/were not impacted by the internet during childhood.

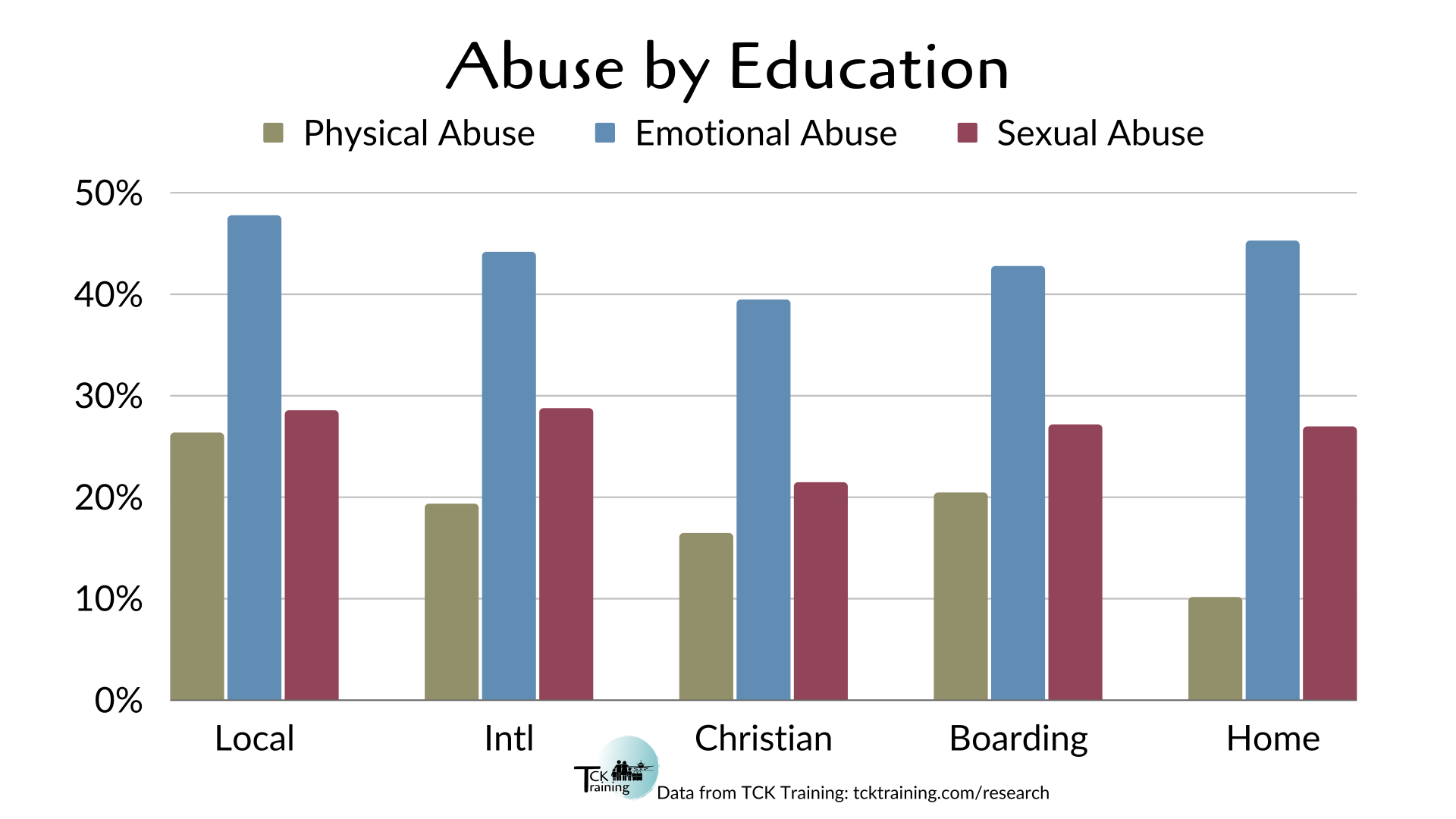

Abuse

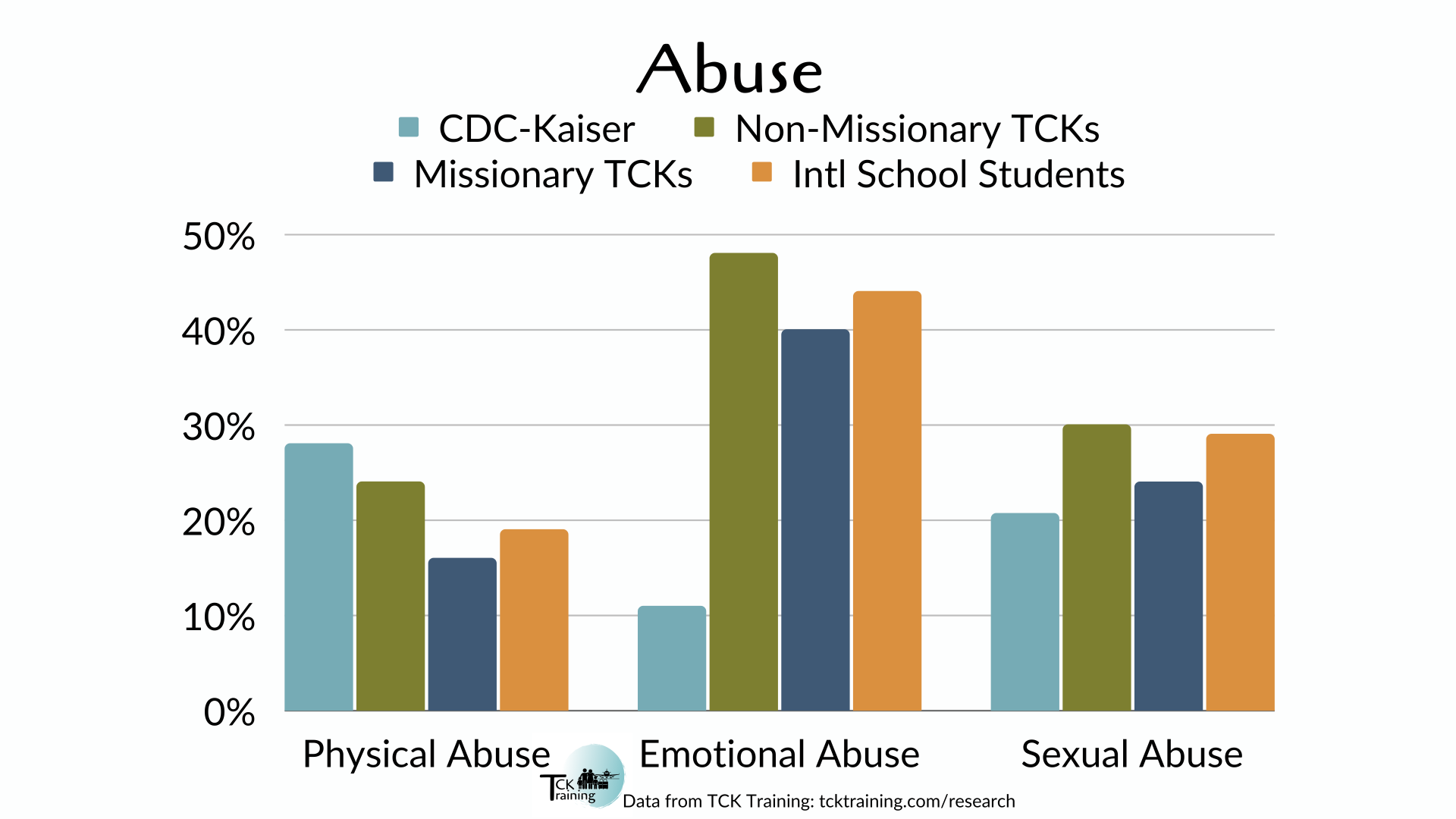

Abuse is broken down into three categories: physical, emotional, and sexual. (The ACE questionnaire records physical and emotional abuse that occurs within the home.) Nearly 1 in 5 TCKs who primarily attended international schools experienced physical abuse; nearly 1 in 3 reported sexual abuse.

44% of international school students experienced emotional abuse at home, four times the rate found among Americans; this was slightly lower than non-missionary TCKs overall, among whom the rate of emotional abuse was 48%. Fewer international school students experienced physical abuse than non-missionary TCKs over all: 24% vs 19% respectively. 29% of international school students reported sexual abuse, similar to 30% of non-missionary TCKs.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

Research into ACEs has taken place worldwide across 25 years. The ten ACE factors are divided into Child Maltreatment (abuse and neglect directly suffered as a child) and Household Dysfunction (factors affecting the childhood living environment). The ACE questionnaire asks about childhood experiences without using the words "abuse" or "neglect" - helpful for catching abusive or neglectful experiences a person would not label that way themselves. We often compare our results to the CDC-Kaiser study of 17,000 Americans, as this is the largest ACE study done worldwide to date. Comparisons with other global populations can be found in our white paper.

We often saw different results across categories among TCKs born before/after 1980 – with the Boomer/Gen X generations on one side, and the Millennial/Gen Z generations on the other. This also separates groups who were/were not impacted by the internet during childhood.

Abuse

Abuse is broken down into three categories: physical, emotional, and sexual. (The ACE questionnaire records physical and emotional abuse that occurs within the home.) Nearly 1 in 5 TCKs who primarily attended international schools experienced physical abuse; nearly 1 in 3 reported sexual abuse.

44% of international school students experienced emotional abuse at home, four times the rate found among Americans; this was slightly lower than non-missionary TCKs overall, among whom the rate of emotional abuse was 48%. Fewer international school students experienced physical abuse than non-missionary TCKs over all: 24% vs 19% respectively. 29% of international school students reported sexual abuse, similar to 30% of non-missionary TCKs.

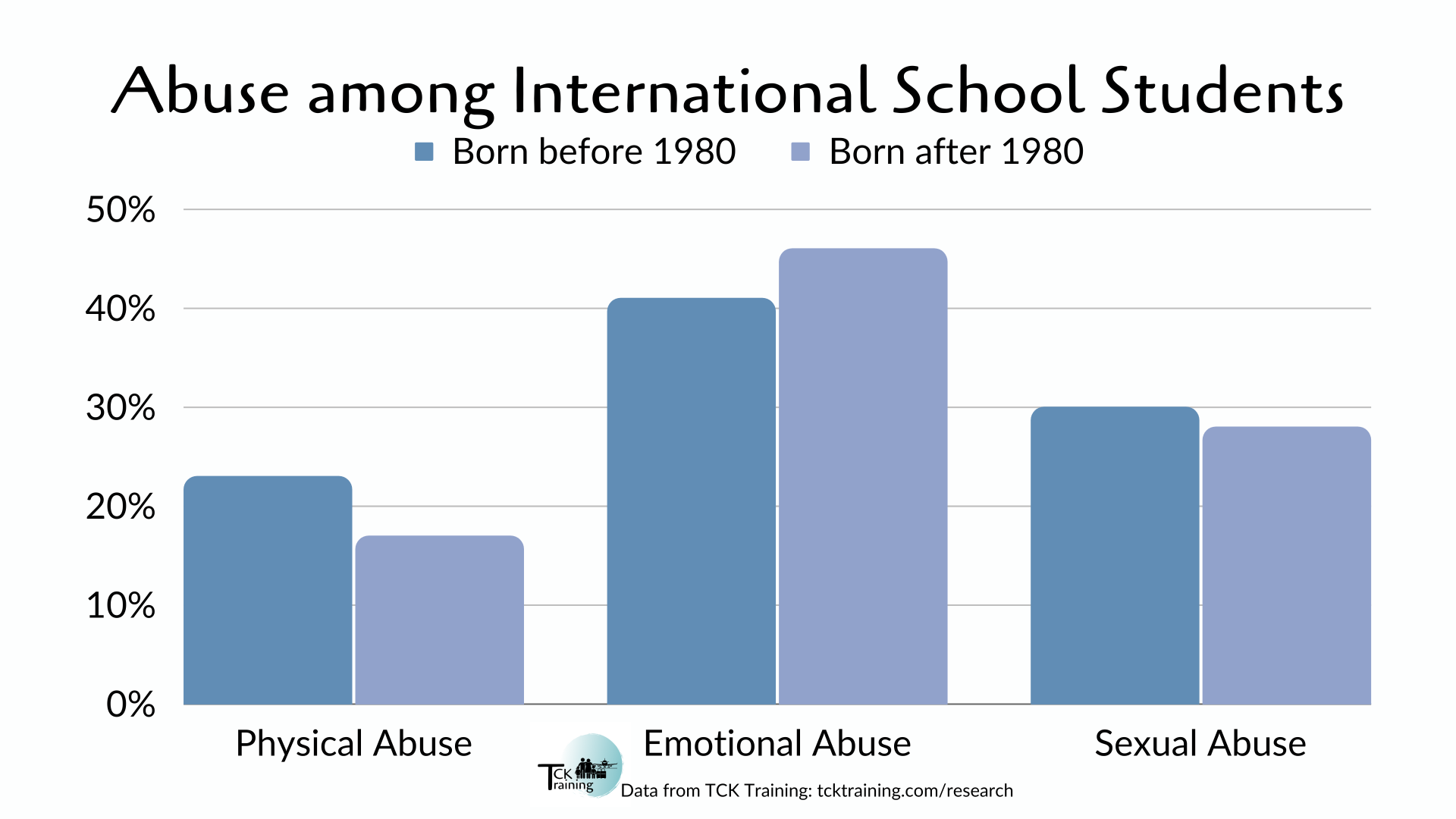

Both physical and sexual abuse rates among international school students decreased over time, whereas emotional abuse increased slightly, from 41% of those born before 1980 to 46% of those born after 1980.

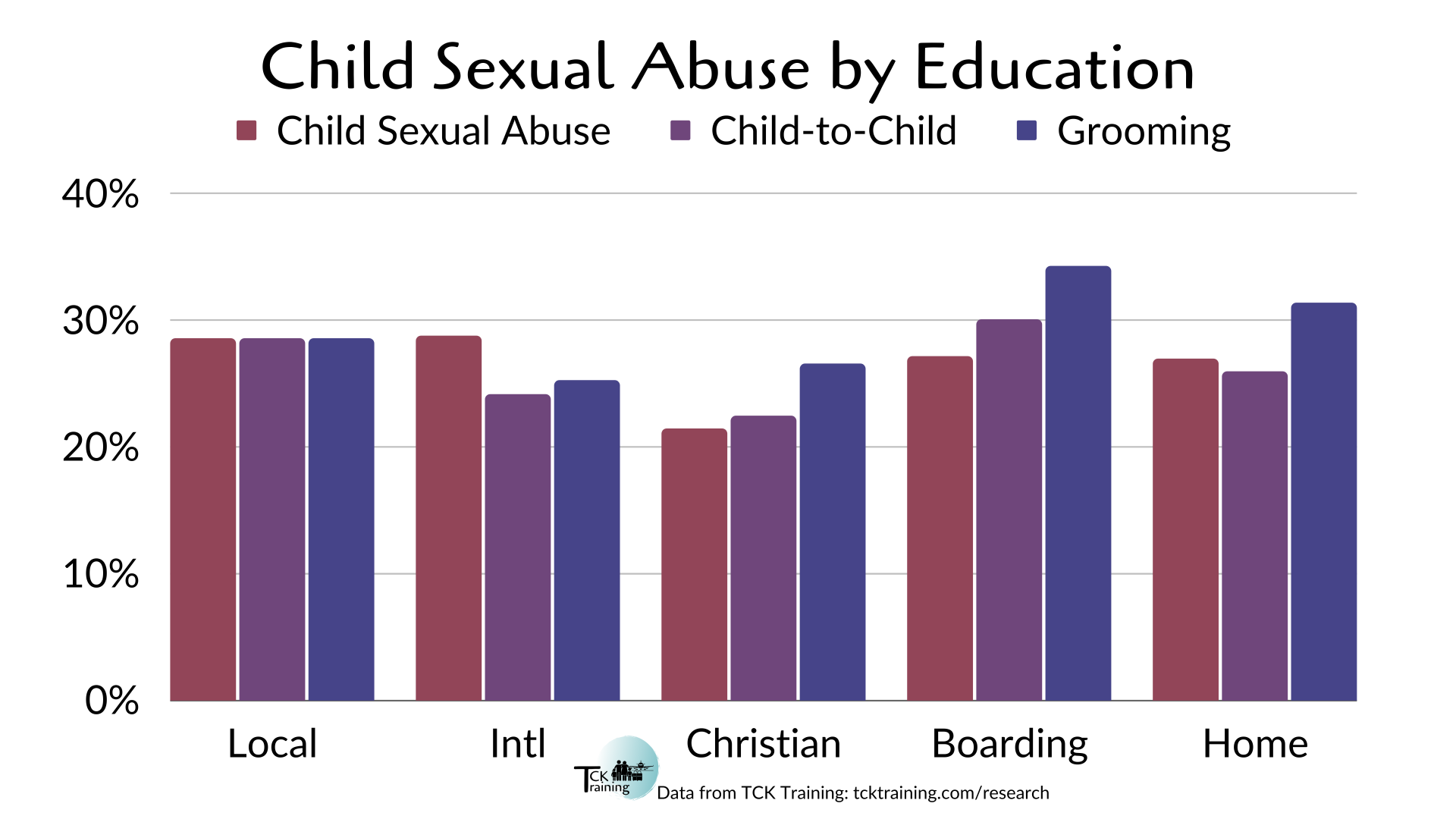

While child-to-child sexual abuse was not included in the original ACE study, it is worth noting due to the lasting effects on survivors. 24% of international school students reported experiencing child-to-child sexual abuse. Child-to-child sexual abuse is a sign that further support may be needed; TCKs who reported child-to-child sexual abuse also had higher rates of emotional abuse (65%), adult-to-child sexual abuse (44%), and emotional neglect (54%).

Another risk factor not included in the ACE questionnaire is grooming. 68% of TCKs who reported grooming also reported experiencing child sexual abuse. 25% of international school students reported grooming behaviors directed toward them by adults. When one quarter of the student body experiences grooming, this is an issue international schools need to address.

During the review process of our survey, experts connected to the international school world discussed the problem of grooming behavior in school settings and particularly a lack of data concerning the prevalence of this. We added a question on grooming in order to gain data about this important issue, even though it would not add to ACE scores themselves.

Neglect

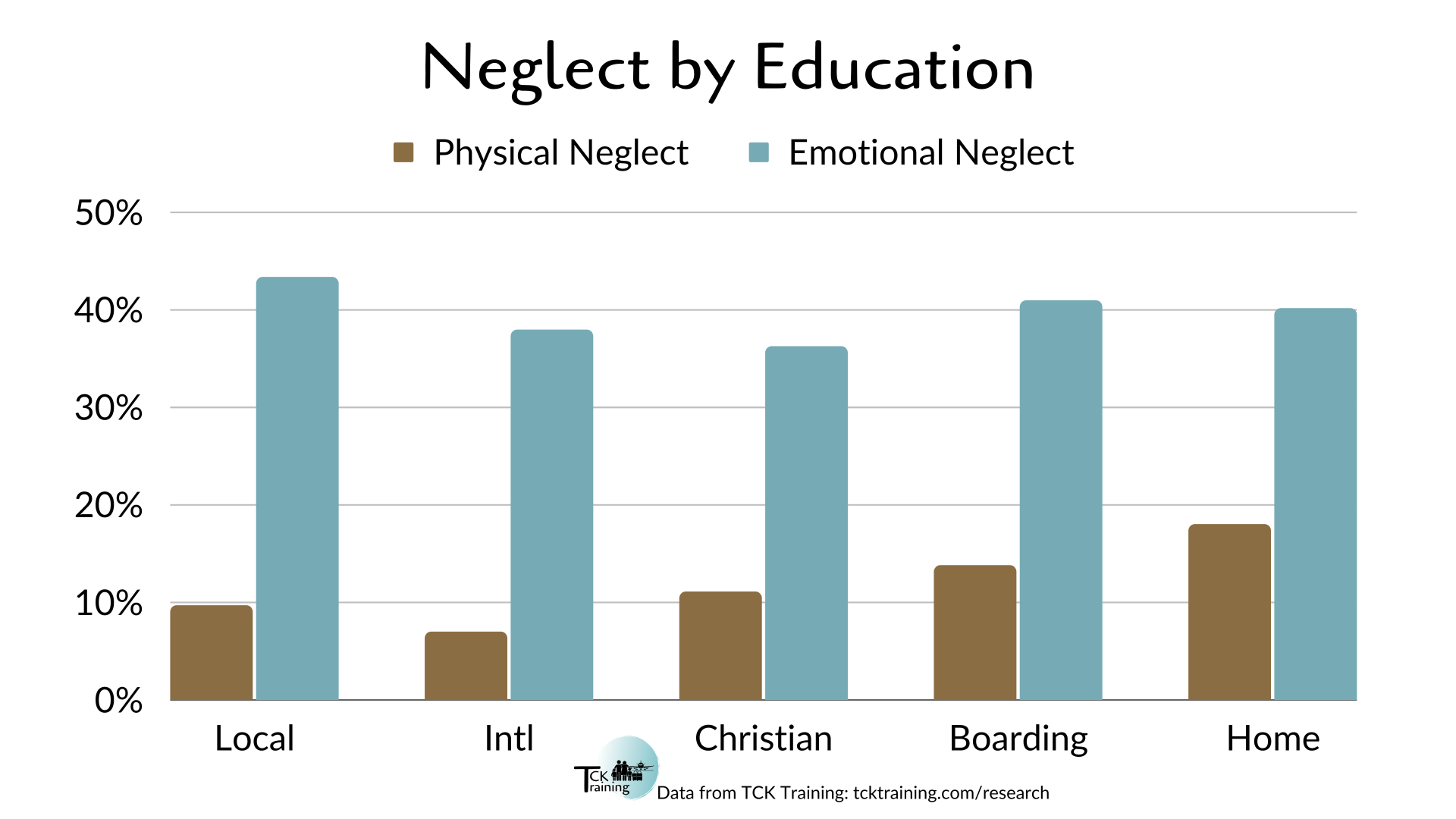

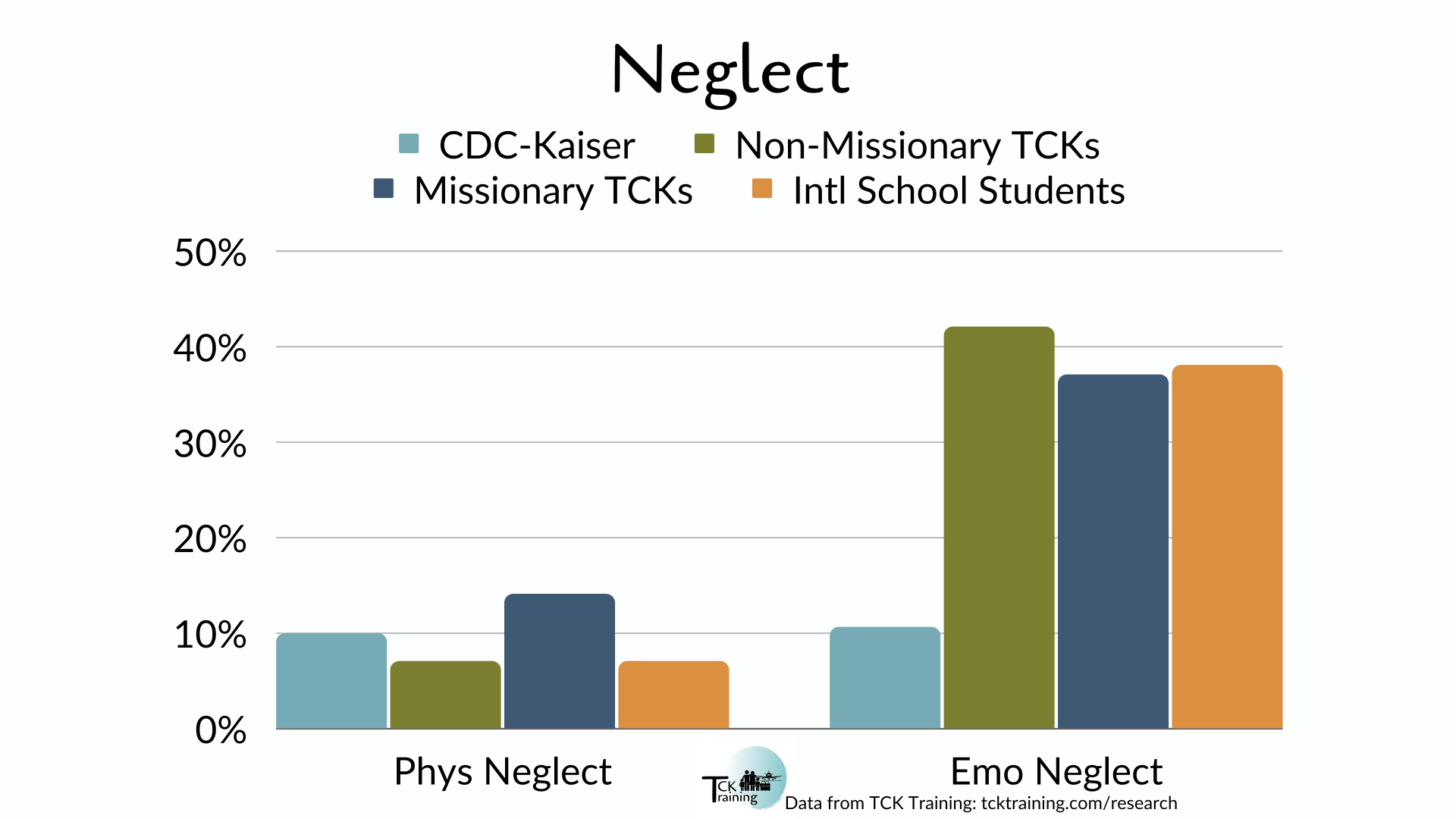

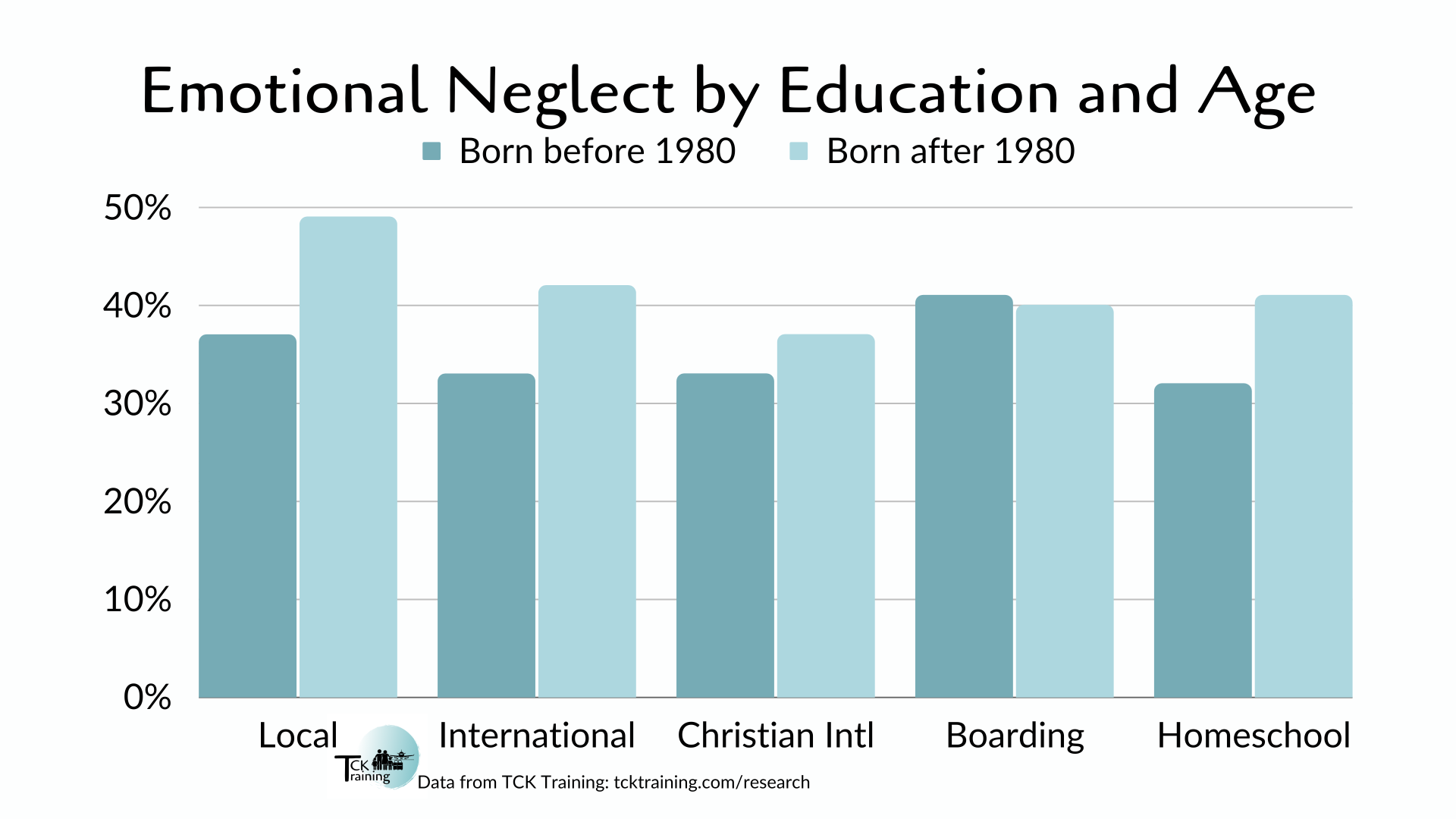

Neglect in the ACE questionnaire is defined through the lens of perception, where a child feels/worries their emotional/physical needs will not be met. While physical neglect is often seen as an extension of poverty, in the ACE context it is not just about what the child has access to but also about their security that provision will continue in the future. In the case of emotional neglect, a child feels unloved or unimportant – whether or not their parents actually do love them. In cases of physical neglect, a child feels their physical needs may not be met – even if they are always fed and cared for. This can look like worry that they will not have enough food, shelter, clean clothing, protection, or medical care. (11%).

Neglect in the ACE questionnaire is defined through the lens of perception, where a child feels/worries their emotional/physical needs will not be met. While physical neglect is often seen as an extension of poverty, in the ACE context it is not just about what the child has access to but also about their security that provision will continue in the future. In the case of emotional neglect, a child feels unloved or unimportant – whether or not their parents actually do love them. In cases of physical neglect, a child feels their physical needs may not be met – even if they are always fed and cared for. This can look like worry that they will not have enough food, shelter, clean clothing, protection, or medical care. (11%).

7% of international school students (and non-missionary TCKs overall) reported physical neglect, compared to 10% of Americans. Nearly 1 in 5 international schools students reported emotional neglect, four times the rate found among Americans.

International school students reported lower rates of emotional neglect than non-missionary TCKs overall (38% compared to 42%). The rate of emotional neglect in international school students increased over time, from 33% to 42%.

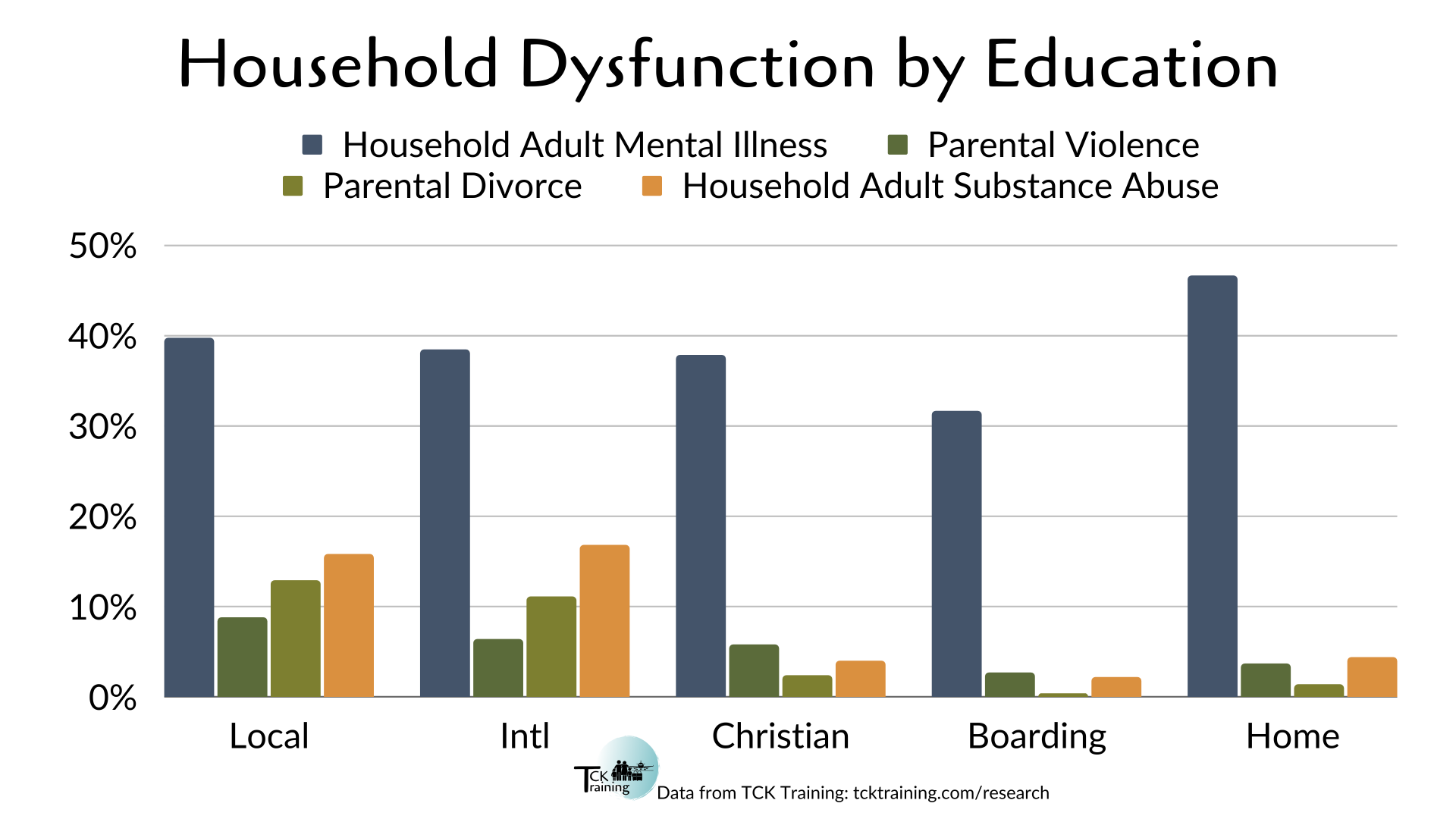

Household Dysfunction

Household dysfunction encompasses household adult mental illness, parental violence, parental divorce or separation, household adult incarceration, and household adult substance abuse. Incarceration was so low among TCKs that we have not included it in this summary.

Household dysfunction encompasses household adult mental illness, parental violence, parental divorce or separation, household adult incarceration, and household adult substance abuse. Incarceration was so low among TCKs that we have not included it in this summary.

6 out of 10 Adverse Childhood Experiences were less common among international school students than among US-based individuals. They were less likely to have an adult household member who was incarcerated or a substance abuser, less likely to have a parent (or step-parent) experience domestic violence, and less likely to have parents separate or divorce. They were also less likely to be physically abused or neglected than US-based citizens.

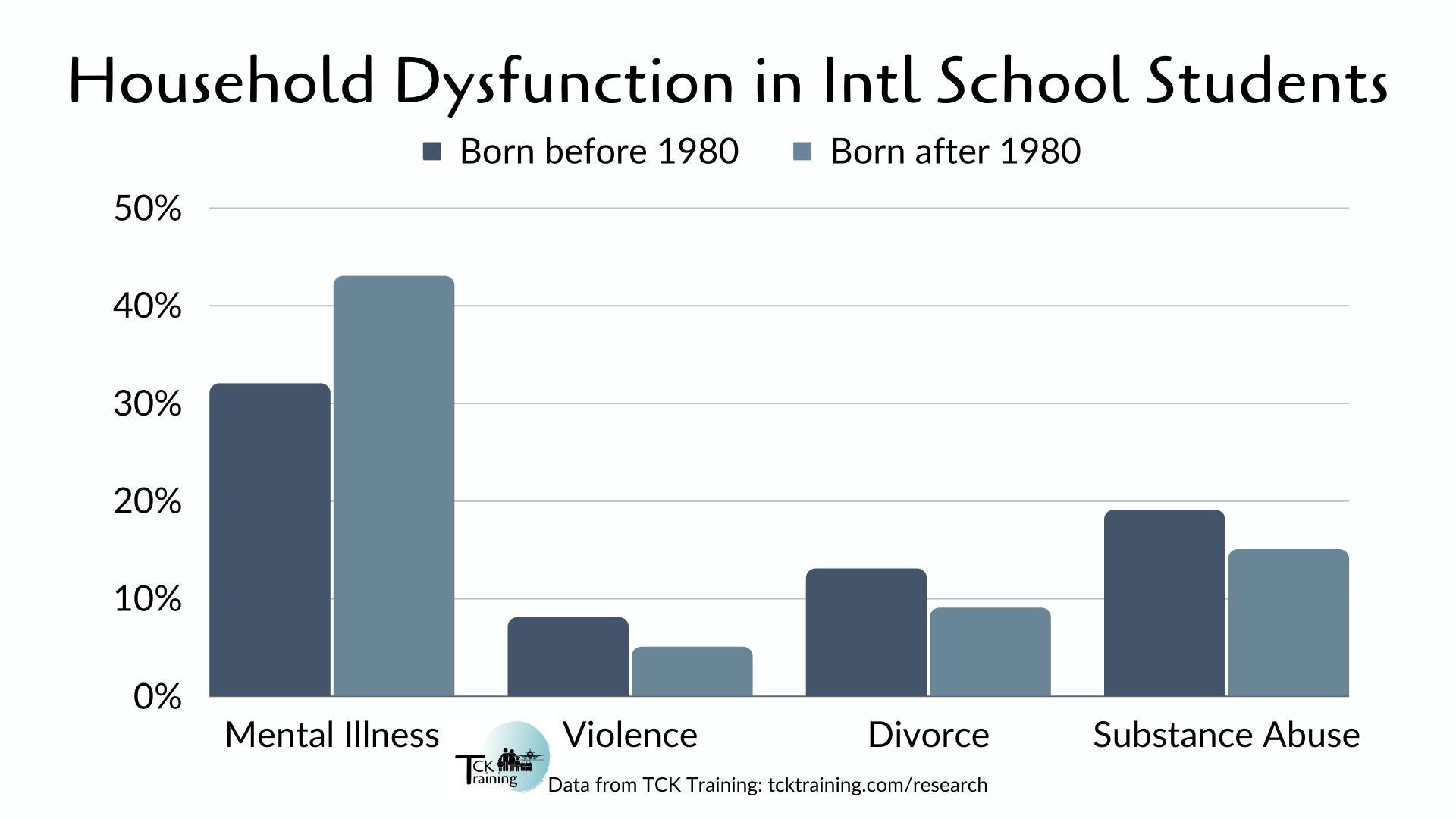

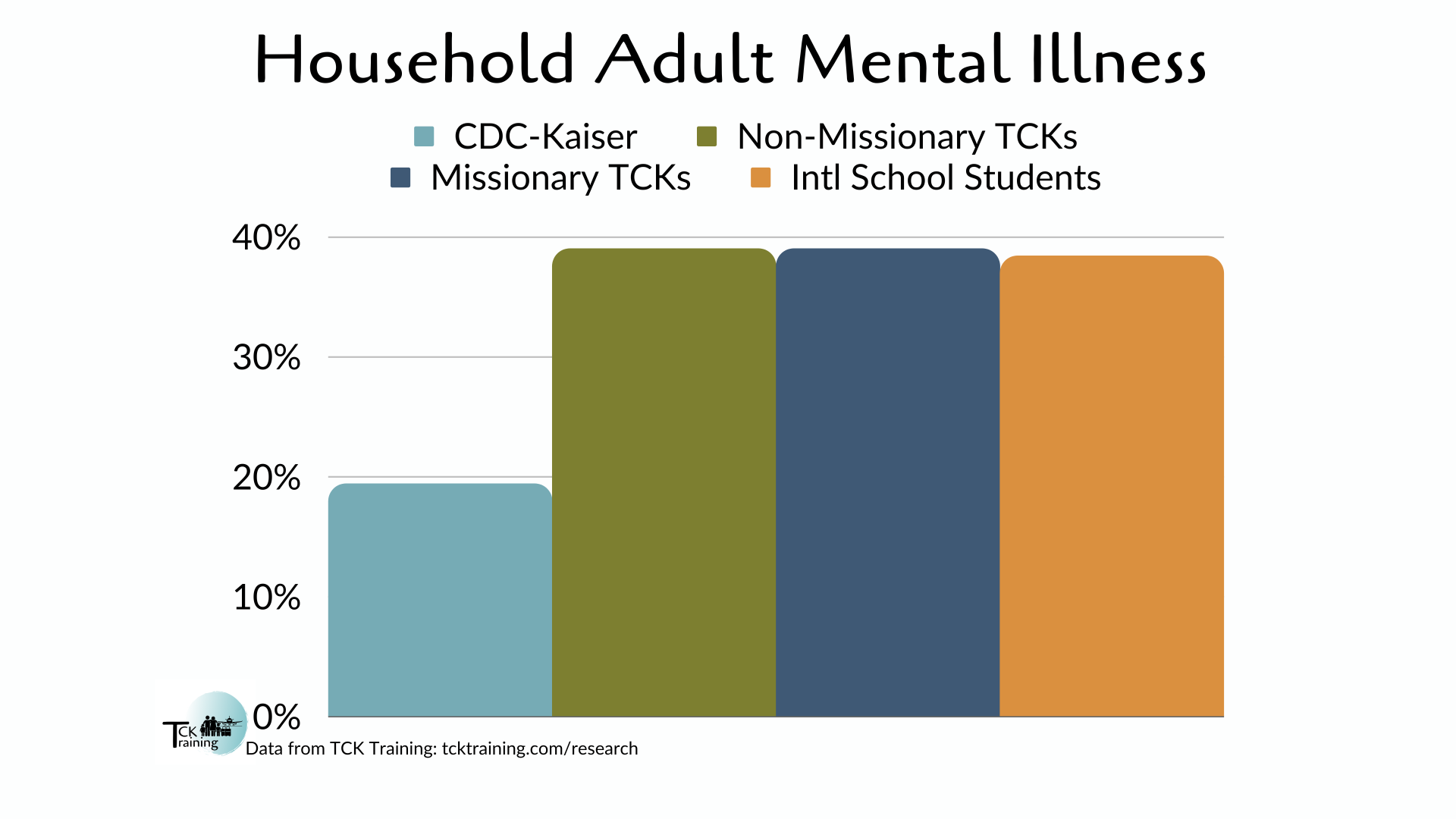

Household Adult Mental Illness

Household adult mental illness is an ACE assigned to anyone who had an adult living in their home during childhood who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide. 1 in 3 Boomers and Gen X international school students (33%) reported household adult mental illness, compared to 42% of Millennials and Gen Z. The overall rate of household adult mental illness among all TCKs (39%) is similar to that of international students overall (38%); this is twice the rate seen in Americans (19%). work, and they need support.

Household adult mental illness is an ACE assigned to anyone who had an adult living in their home during childhood who was depressed, mentally ill, or attempted suicide. 1 in 3 Boomers and Gen X international school students (33%) reported household adult mental illness, compared to 42% of Millennials and Gen Z. The overall rate of household adult mental illness among all TCKs (39%) is similar to that of international students overall (38%); this is twice the rate seen in Americans (19%). work, and they need support.

The high rates of adult mental illness among international school families demonstrates that many expatriate families are under stress and need support.

Parents in international communities especially must be empowered to care for their own emotional needs, recognising this as vital for the long-term thriving of their children. Pushing through hurts not only yourself, but also your ability to show up for your children.

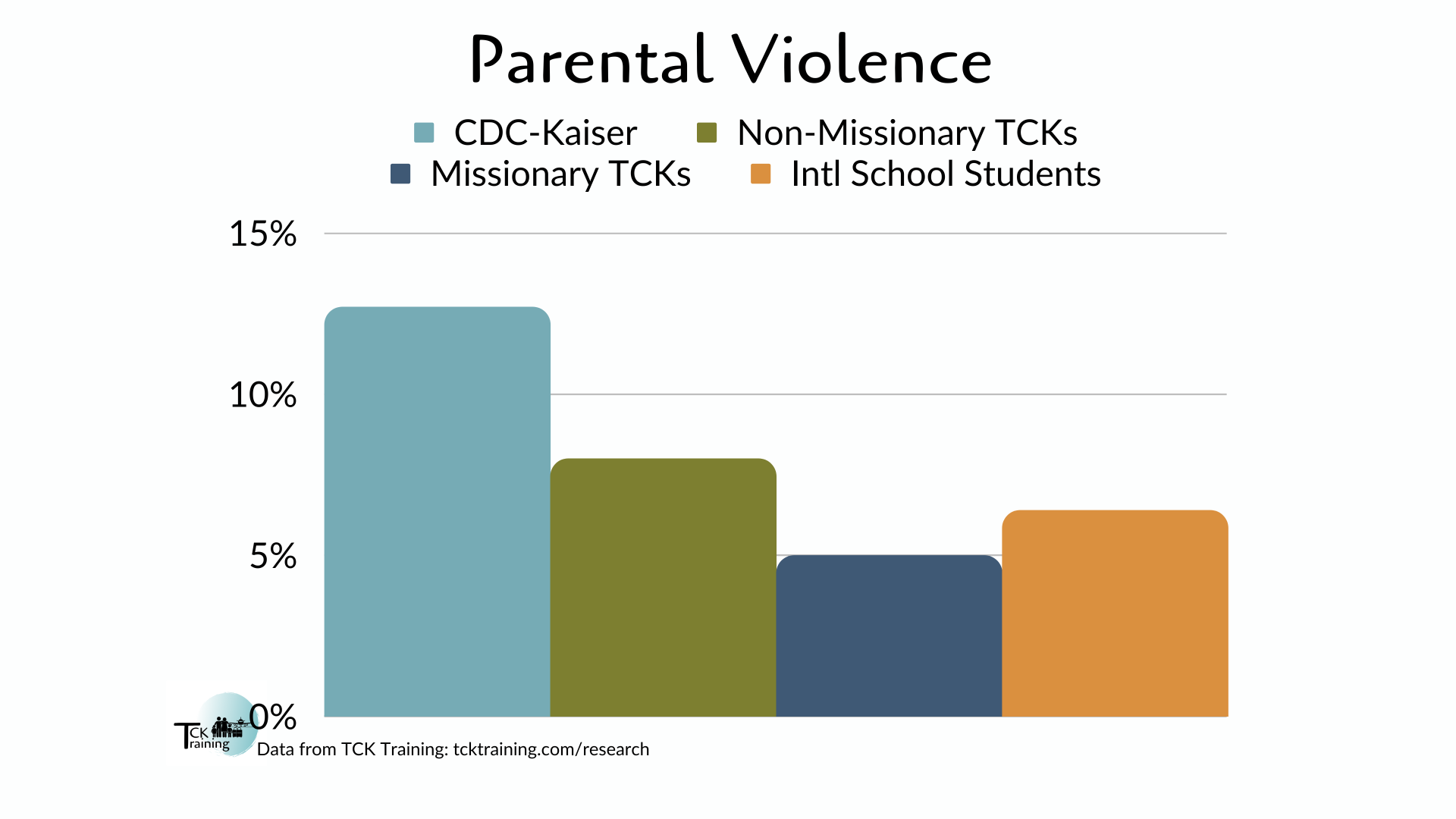

Parental Violence

Parental violence is defined as a child being impacted by, even if not actually witnessing, violence toward a mother/step-mother or father/step-father. 6% of international school students reported parental violence. This rate decreased over time; 8% of older generations and 5% younger generations of international school students reported parental violence. International school students experienced parental violence at half of the rate found among Americans, and at a slightly lower rate than other non-missionary TCKs, 6% vs 8% respectively.

Parental violence is defined as a child being impacted by, even if not actually witnessing, violence toward a mother/step-mother or father/step-father. 6% of international school students reported parental violence. This rate decreased over time; 8% of older generations and 5% younger generations of international school students reported parental violence. International school students experienced parental violence at half of the rate found among Americans, and at a slightly lower rate than other non-missionary TCKs, 6% vs 8% respectively.

While 5% is a low number, and great to see, that still represents 1 in 20 children – suggesting that on average, one student in each international school classroom lives in a family impacted by violence. The support needed can be challenging to find while living abroad, but it is vital to extend services to these families in crisis.

It is vital that everyone who cares for TCKs be educated on what domestic abuse is, how to recognize it, and how to support families and children when domestic abuse is present.

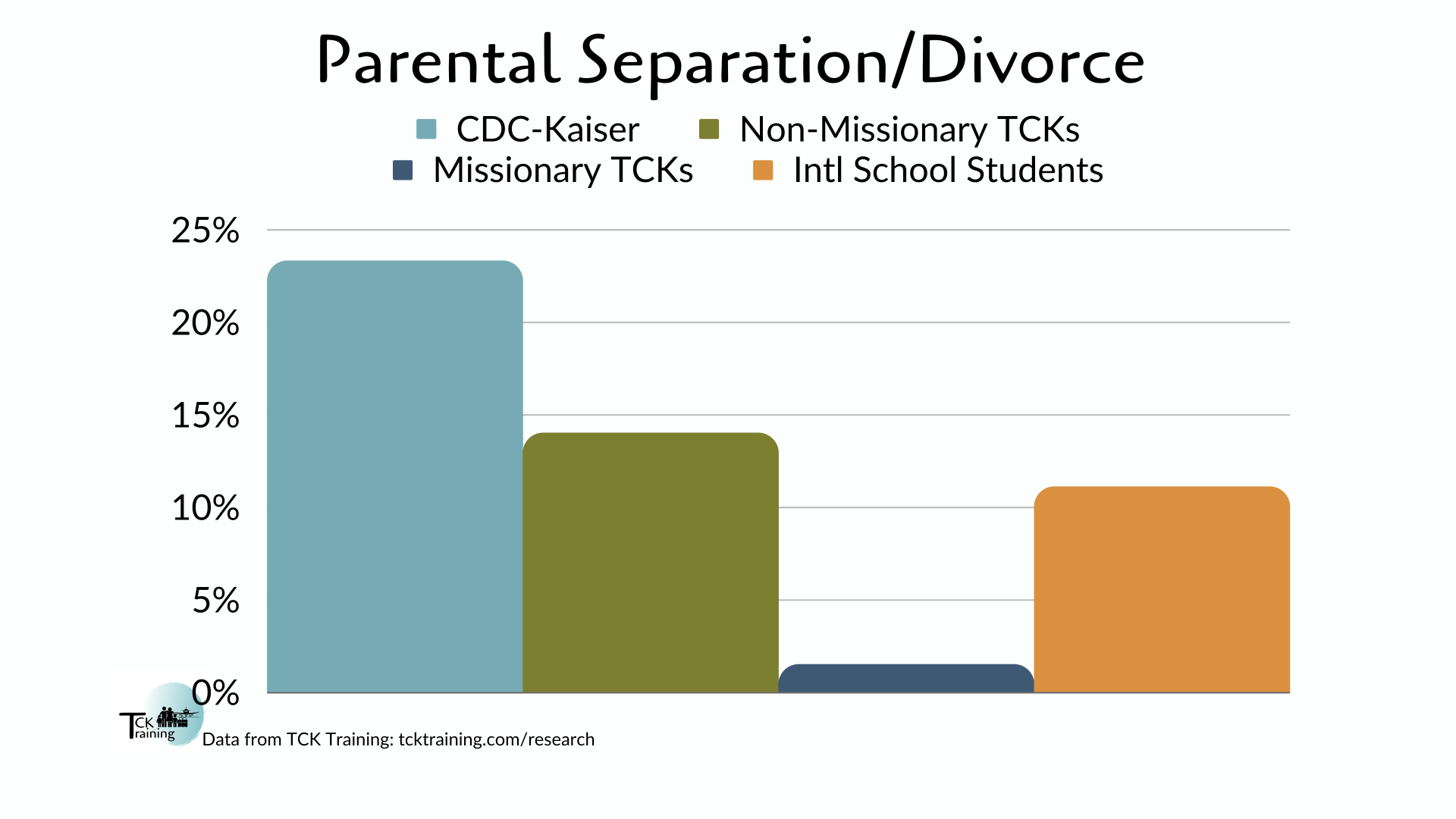

Divorce/Separation

The rate of parental divorce/separation was 23% in the CDC-Kaiser study, but much lower among TCKs. 11% of international school students experienced parental divorce/separation before age 18, slightly lower than 14% of non-missionary TCKs overall. There was also a decrease in the divorce rate of international school families over time (13% vs. 9%). A lower divorce rate does not necessarily guarantee stronger marriages, unfortunately.

The rate of parental divorce/separation was 23% in the CDC-Kaiser study, but much lower among TCKs. 11% of international school students experienced parental divorce/separation before age 18, slightly lower than 14% of non-missionary TCKs overall. There was also a decrease in the divorce rate of international school families over time (13% vs. 9%). A lower divorce rate does not necessarily guarantee stronger marriages, unfortunately.

There are factors that make divorced employees less likely to seek or be awarded an overseas assignment. There are also outside factors that make divorce less accessible or less appealing to expats. A divorce is a legal proceeding, and managing this while living a global life is complex, especially when work visas and custody of children is involved.

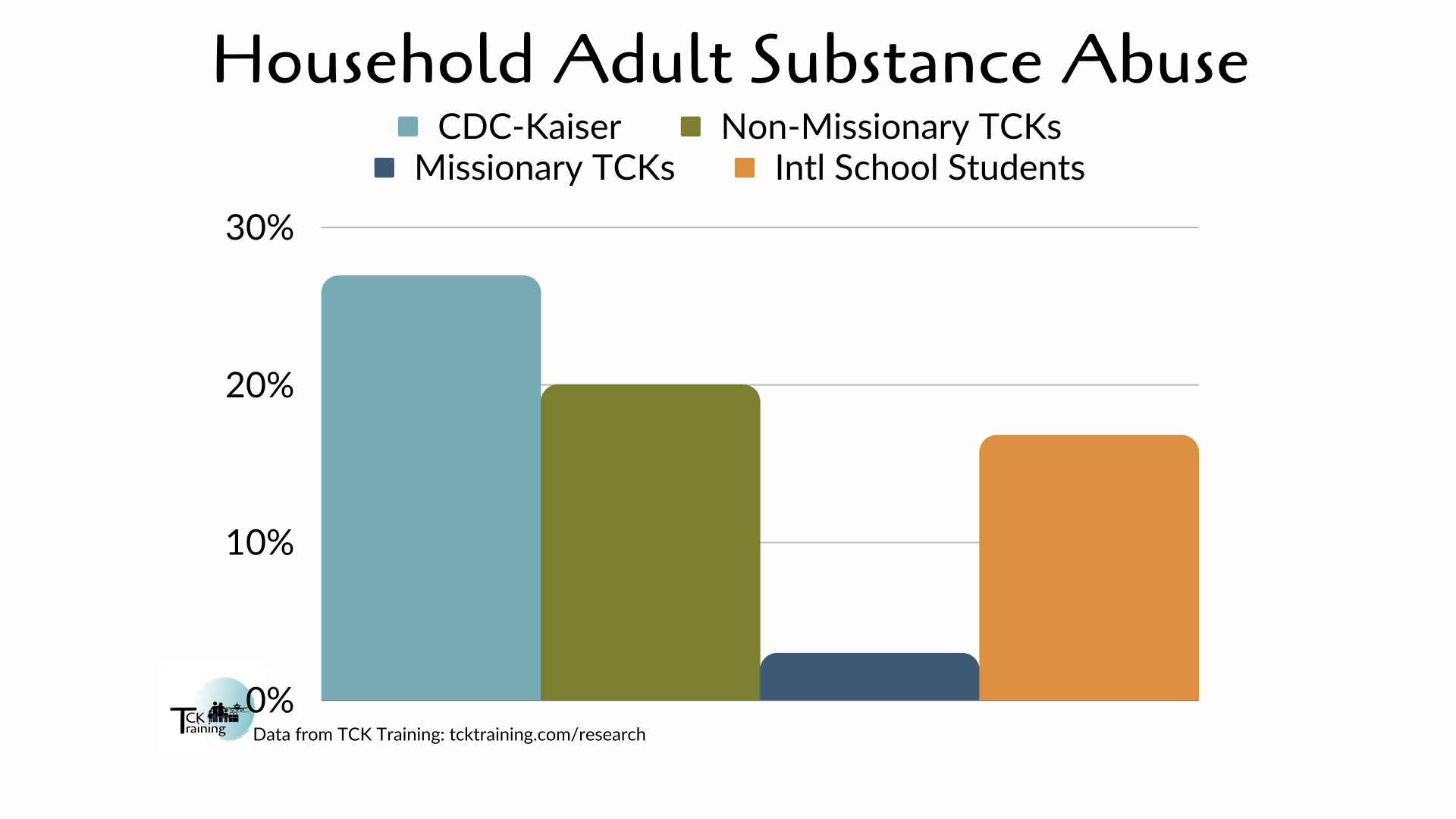

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse as an ACE factor required that an adult living in the home was an alcoholic or used illicit drugs. 17% of international school students reported household adult substance abuse, slightly less than the 20% of non-missionary TCKs overall. The rate decreased over time, from 19% to 15%. Substance abuse can be another sign of families under stress, in need of care and support.

Going by the lower rate seen in the younger generations of TCKs, an international classroom might include on average three students for whom alcoholism or substance abuse are happening at home.

Substance abuse as an ACE factor required that an adult living in the home was an alcoholic or used illicit drugs. 17% of international school students reported household adult substance abuse, slightly less than the 20% of non-missionary TCKs overall. The rate decreased over time, from 19% to 15%. Substance abuse can be another sign of families under stress, in need of care and support.

Going by the lower rate seen in the younger generations of TCKs, an international classroom might include on average three students for whom alcoholism or substance abuse are happening at home.

Risk Mitigation

While this data can seem discouraging, there is hope – and ways to mitigate the risks we’ve talked about. Globally mobile families need support in order to meet their children’s needs and ultimately thrive. These challenges and risks are not unsolvable or reasons to despair, but rather reasons to take action in intentional ways that reflect the urgency of the matter.

In TCKs at Risk we outline a number of ways that organizations can protect children and support families. For example, additional research into Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs) gives a roadmap for effectively buffering children from difficulties they face.

While this data can seem discouraging, there is hope – and ways to mitigate the risks we’ve talked about. Globally mobile families need support in order to meet their children’s needs and ultimately thrive. These challenges and risks are not unsolvable or reasons to despair, but rather reasons to take action in intentional ways that reflect the urgency of the matter.

In TCKs at Risk we outline a number of ways that organizations can protect children and support families. For example, additional research into Positive Childhood Experiences (PCEs) gives a roadmap for effectively buffering children from difficulties they face.

Simple intentionality in parenting, policies, and procedures can mitigate the risk and increase the chances of positive, healthy outcomes for Third Culture Kids… When a person had four or more Adverse Childhood Experiences, also having at least six of these Positive Childhood Experiences lowered the risk for depression in adulthood by 72%.

With 22% of international school students reporting 4 or more ACEs, these buffering protections are particularly important. (Source: Caution and Hope for International School Students).

It is valuable for those of us working in the international education field to have access to research grounded in international life. Knowing what our students are statistically likely to face and what interventions are best placed to lower risks and increase resilience is of great benefit. PCEs help develop resilience, and emotional regulation is of particular importance given the ACE factors that are high among TCKs.

Child protection is essential, and school-wide strategies should be put in place to safeguard children. The child protection strategies a school offers is an important factor for parents to research and consider when choosing a school for their children. While child protection laws differ from country to country, many international schools are holding themselves to higher standards than ‘required’ by national law. Accreditation bodies are also beginning to include child protection standards in their requirements.

Robust child safety policies don’t end with hiring or initial onboarding but also include ongoing frequentative trainings in child safety principles for everyone who might encounter children. This training sets up an expectation of how children should be treated, including prevention or ‘above-reproach’ strategies, such as not being alone with a child. These safeguards can help people without intent to harm to succeed in their best intentions, can help people identify suspicious behavior, and can promote healthy vigilance in the protection and safeguarding of children.

International schools are also perfectly placed to provide care to globally mobile families. Many families receive little to no transition training or other support of this kind pre-departure, if at any time during their international assignment, unless they find and fund their own training. When international schools take up the opportunity to educate their school community about the risks of international life and how to mitigate these risks, this preventive care improves outcomes for everyone.

International schools who genuinely care about student welfare and long-term thriving for their students will invest in margin/mental health support for their staff, and preventive care resourcing for their parent community.

Whether you are a parent, educator, or school administrator, TCK Training is here to help! We offer a range of training and support, both organization-wide and for individual families. We have a full range of virtual and in-person services for international schools, including our Virtual Training Courses for International School Staff, Sexual Abuse Awareness Training, and Preventing TCK Neglect as an Organization. Parents seeking direct support can benefit from workshops such as Understanding Emotional Abuse and Neglect as a Parent, Risk Prevention for Highly Mobile Families, and Raising Healthy TCKs. And we have a whole range of services specifically for international schools!

References:

- Caution and Hope: The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids (Crossman and Wells, 2022. TCK Training.)

- TCKs at Risk: Risk Factors and Risk Mitigation for Globally Mobile Families (Crossman, Wells and Vahey Smith, 2022. TCK Training.)

- Caution and Hope for International School Students (Blog post, Crossman. TCK Training, 2022.)

- Hidden Struggles of International Students: Adversity Amid Privilege (Blog post, Crossman. Eleni Vardaki, 2022.)

- Data-driven interventions for Third Culture Kids (Kogelmann and Crossman, International School Leader Magazine, 2022).

- Third Culture Risk (Crossman, International Teachers Magazine, 2022).

Empty space, drag to resize

Related blog posts:

Caution and Hope for International School Students

Other blog posts in this series:

Caution and Hope for International School Students

Other blog posts in this series:

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Diplomat Kids

- Mitigating Risk Factors for International Business Kids

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Military Kids

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Children of International Educators and Humanitarian Workers

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Mission Kids

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Homeschooled TCKs

- Mitigating Risk Factors for Christian International School Students

About the Authors

Tanya Crossman grew up in Australia and the US before moving to China at age 21; she has worked with TCKs for 20 years. She is the Director of Research and International Education at TCK Training.

Lauren is an adult TCK who grew up in East Africa and has spent nearly 10 years working with TCKs in the U.S. Her experiences have fueled her passion for supporting TCKs through preventative care that fosters healthy, thriving adults. She holds a Master’s in Public Health.

AT TCK TRAINING MARCH IS

Caregivers Appreciation Month!

See how YOU can celebrate

Free resources, giveaways, sales & more!

Free resources, giveaways, sales & more!